- Home

- Valery Bruisov

The Fiery Angel Page 2

The Fiery Angel Read online

Page 2

In the spring of the following year, the lieutenant of the Spanish detachment, Don Miguel de Gamez, approached me to his person as physician, because I had gained a certain familiarity with the Spanish language. Together with Don Miguel I had to travel to Spain, whither he was despatched with secret letters to our Emperor, and this journey resolved my fate. Having found the court at the City of Toledo, we found there also the greatest of our contemporaries, a hero equal to the Hannibals, Scipios and other great men of antiquity—Hernando Cortes, the Marquis del Valje-Oaxaca. The reception arranged for that proud conqueror of Empires, as well as the narratives of those who had returned from the country so entrancingly described by Amerigo Vespucci, persuaded me to seek my fortune in that blessed haven for all the failures of this earth. I joined a friendly expedition, organised by German settlers in Seville, and set sail with light heart across the Ocean.

In the West Indies I entered at first the service of the Royal Audiencia; but soon, having seen proof of how unfaithfully and unskilfully it conducts its affairs, and of how unjustly it rewards abilities and services, I chose rather to execute commissions for those German houses that have factories in the New World, for preference for the Welzers who own copper mines in San Domingo, but also for the Fuggers, the Ellingers, the Krombergs and the Tetzels. Four times I made forays to the West, to the South and to the North, searching for new veins of ore, for fields of gems—amethysts and emeralds, and for a forest of precious timbers: twice under the command of others, and twice personally commanding the expeditions. In this way I marched through all the lands from Chicora to the port of Tumbes, spending long months among the dark-skinned heathen, beholding in the log-palaces of the natives riches so vast that before them the treasures of our Europe are as nothing, and several times escaping the destruction that hung over me as if almost by a miracle. In my love for an Indian woman, who concealed beneath her dark skin a heart that could feel both attachment and passion, it was my lot to experience powerful agonies of soul, but it would be out of place to relate of them here at greater length. I may say in short—that, just as those soft twilight days spent at the books with dear Friedrich educated my thoughts, so these terrible years of wandering tempered my will in the flame of trial, and endowed me with that most priceless attribute of man—faith in myself.

It is certainly quite erroneous for people in our country to imagine that across the Ocean gold is to be gathered from the earth merely by stooping down, but, none the less, after spending five years in America and the West Indies, I contrived, by unremitting industry and toil and not without the help of luck, to put by an adequate sum in savings. And it was then that the thought came to me to travel back to German lands, not with the object of settling peacefully in our almost sleepy township, but with the worldly desire to parade my successes in front of father, who could not but think of me as the ne’er-do-weel who robbed him. I shall not conceal, however, the fact that I was also filled with a burning longing and weariness for home, that I had never thought to feel for my native mountains, on whose slopes, embittered, I used to wander with my arbalist, and that I passionately wanted to see my dear mother, as well as the friend whom I had left behind, and whom I hoped to find still alive. Even then, however, I was firmly decided that, after having visited the home village and re-established connection with the family, I should return to New Spain, which I regarded as my second fatherland.

In the early spring of the year ’34, I sailed away in a ship of the Welzers from the port Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz, and after a stormy and difficult journey we arrived in the wealthy city of Antwerpen. Several weeks of my time were spent in accomplishing the various commissions I had undertaken to fulfil, and it was only in the month of August that, at last, I could set out upon the journey to the Rhine lands. From that moment, properly, begins my narrative.

Chapter the First

How I first met Renata and how she related to me her Whole Life

FROM the Netherlands I decided to go overland, and I chose the route through Köln, for I wanted to see once more that city in which I had known so many pleasant hours. For thirty Spanish escudos I bought an excellent horse, capable without strain of carrying both me and my baggage, but, fearing robbers, I tried to assume the appearance of a simple sailor. I exchanged the gay and relatively sumptuous dress in which I had strutted about in luxurious Brabant for the outfit of an ordinary seaman, dark brown in colour and with breeches tied below the knee. But I retained my reliable long sword; for I placed no less faith in it than in Saint Gertruda, patroness of all land travellers. I set aside a small sum in silver joachimsthalers for my expenses on the journey, and my savings I sewed in the lining of a broad belt in golden pistoles.

After a pleasant five days’ journeying in the company of casual strangers, for I travelled without undue haste, I crossed the Maas at Venloo. I will not conceal the fact that when I reached the regions where German dresses began to flicker past me, and my hearing was assailed by the glib—oh, so familiar—speech of home, I was seized by emotions perhaps unworthy of a full-grown man! Leaving Venloo early, I reckoned to reach Neuss by the evening, and accordingly I took leave of my road companions at Viersen, for they purposed visiting Gladbach on the way, and turned, already alone, on to the Düsseldorf highway. As there was need to hasten I began to urge on my horse, but stumbling, it injured its ankle against a stone—and this insignificant occurrence gave rise, as direct cause, to the long series of remarkable happenings that it became my fate to live through after that day. But I had long observed that it is only insignificant happenings that prove the first links of those chains of heavy trial which, unseen and unheard, life sometimes forges for us.

On a lame horse I could advance but slowly, and I was still far outside the town when it became difficult to see in the grey twilight, and from the grass there rose a pungent mist. I was riding at that time through a thick beech forest, and was foreseeing not without misgivings a night spent in a place totally unknown to me, when suddenly, rounding a bend, I espied, in a small clearing at the very edge of the road, a little wooden house, all asquint, lonely, and as if it had lost its way. The gate was closely shut and locked, the lower windows more like large arrow-slits, but under the roof there dangled on a rope a half-broken bottle, indicating that here was a hostelry, and, riding up, I began to hammer on the shutters with the hilt of my sword. At my firm knocking, and at the furious barking of the dog, the hostess peered out, but for a long time she refused to let me in, questioning me as to who I was, and why I rode that way. All unsuspecting what future I was demanding for myself, I insisted with threats and with curses, so that at last a door was unlocked to me and my horse led away to its stall.

Up a rickety staircase, in darkness, I was conducted to a tiny room on the second floor, narrow and uneven in width, like the case of a viola. Whilst in Italy a softly laid bed, and an appetising supper with a bottle of wine, can always be found even in the cheapest hotels, travellers in our country—except the rich, who carry dozens of stuffed bales with them on mules—still have to be content with black bread, inferior beer and a night on old straw. Stuffy and narrow seemed my first shelter in my native land to me, especially after the clean, almost polished bedrooms in the houses of the Netherland merchants whose doors had been opened to me by my letters of recommendation. But I had experienced worse nights indeed during my arduous travels across Anahuac, so, drawing my leather cape about me, I tried as soon as possible to nod my head off into sleep, not heeding a drunken voice that sang in the lower hall a song new to me, the words of which, however, became fixed in my mind:

Ob dir ein Dirn gefelt

So schweig, hastu kein Gelt.

How surprised should I have been, if, as I fell asleep, some prophetic voice had told me that this was to be for me the last evening of one life, after which another was to begin! My fate, having transported me across the Ocean, had held me on my journey exactly the right number of days, and then brought me, as if to a destined march-stone, to

this house so distant from town and village, where the fatal meeting awaited me. A learned Dominican monk would have seen in it the obvious expression of the will of God; an enthusiastic Realist would have found in it reason to deplore the complicated linkage of causes and effects, that do not fit into the revolving circles of Raymundus Lullius; while I, when I think of the thousands and thousands of chances that were necessary for me to chance that very evening on my way to Neuss into that small wayside inn—I lose all sense of differentiation between the ordinary and the supernatural, between miracula and natura. I can only suppose that my first meeting with Renata was, in a smaller way, just as miraculous as all the marvels and buffetings that later we lived through together.

Midnight, probably, had long passed, when I suddenly awoke, roused all at once by something unexpected. My room was bright with the silver-blue light of the moon, and the stillness around was as if all earth, and heaven itself, had died. But then, in this stillness, I distinctly heard in the next room, behind a partition of planks, a woman whisper and cry out feebly. Though wise is the proverb that says the traveller bears enough to worry about on his own back and should not pity the shoulders of others, and though I have never been distinguished by exaggerated sentimentality, yet the love of adventure, to which I have been inclined since childhood, could not fail to rouse me to the defence of a lady in distress, to protect whom, indeed, as a man who had spent whole years in battle, I had a knightly claim. Rising from bed and unsheathing my sword half way, I left my room and, even in the dark passage in which I found myself, easily distinguished the door to the room from which the voice had come. I asked loudly whether anyone required protection, and, when I had repeated these words a second time and no one had replied, I thrust at the door, breaking a small bolt, and entered.

It was then that I beheld Renata for the first time.

In a room as cheerless as my own and also lit brightly by the moonlight, there stood, in shaking terror, a woman stretched against the wall, her hair loose and flowing. No other human being was there, for all the corners of the room were clearly lit and the shadows lying on the floor were clear-cut and distinct; and yet, shielding herself, she thrust out her arms in front of her as if someone were advancing towards her. In this movement there was something terrifying in the extreme, for one could not fail to understand that she was threatened by some invisible apparition. Seeing me, the woman, uttering a fresh cry, rushed to meet me, fell on her knees before me as if I were a messenger from Heaven, seized me convulsively and said, panting:

“At last it is you, Rupprecht! I have no more strength!”

Never, before that day, had Renata and I met, and she saw me as much for the first time as I saw her, and yet she called me by my name as simply as if we had been friends from childhood. I tried not to show my surprise and, laying my hand lightly on her shoulder, asked whether it were true that she was being pursued by an apparition. But the woman had no power to answer me and, weeping and laughing by turns, she pointed with her trembling hand where, to my eyes, there was nothing but a ray of moonshine. I must not here deny that the unusual nature of all the surrounding circumstances, together with the consciousness of the presence of inhuman powers, had seized my whole being with a dull terror that I had not experienced since early youth. More to soothe the frantic lady than because I myself believed in the efficacy of the act, I unsheathed my sword completely, and, grasping it by the blade, I pointed the cross-like hilt before me, repeating some mystic words taught me by an Indian who invoked the demon Anjan. But the woman, beginning to tremble, fell on her face as if in a convulsion of imminent death.

I did not think it proper to my honour to flee from thence, though I realised immediately that an evil demon had now taken possession of the unfortunate creature and was fearfully tormenting her from within. I swear by the pure blood of Christ—never till that day had I witnessed such convulsions nor suspected that a human body could be so incredibly distorted! The woman stretched out painfully and in defiance of all natural usage, so that her neck and breast became as firm as wood and as straight as a cane, then she suddenly bent forward so that her head and chin approached her toes and the veins in her neck became monstrously taut, then, by reversal, she miraculously thrust herself backwards, and the nape of her neck became twisted inside her shoulder, towards the small of her back and her thigh high raised. I watched these ecstasies of torment as if made of stone, practically without horror and without curiosity, as I would watch a representation of the torments that await us in hell.

Then the woman ceased to knock herself against the hard planks of the floor, and the distorted features of her face little by little became more endowed with reason, but she still bended and unbent convulsively, again protecting herself with her hands, as if from an enemy. I guessed then that the Devil had come out of her and was outside her body and, drawing the woman to me, I began to repeat the words of the holy prayer that, I have heard, is always employed at exorcisms: Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna. In the meantime the moon was already setting beyond the tops of the forest, and, in measure that the morning twilight took possession of the room, shifting the shadow from the wall to the window, the woman who lay in my arms came gradually to. But the darkness still breathed on her, like the cold tramontana of the Pyrenean Mountains, and she trembled all over as if from the frost of winter.

I asked: had the spirit departed.

Opening her eyes and glancing round the room, as if recovered from a swoon, she answered me:

“Yes, he dissolved, for he saw that we were well armed against him. He can attempt nothing against a strong will.”

These were the second words that I had heard from Renata. Having uttered them, she began to weep, shivering in a fever, and she wept so that the tears rolled down her cheeks without restraint and moistened my fingers. Reflecting that the lady would not recover warmth on the floor, and in a measure reassured, I raised her without effort, for she was of small stature and slight, and carried her to the bed that stood near by. There I covered her with a coverlet that I found in the room and tried to soothe her with quiet words.

But the woman, still weeping, became seized by yet another access of excitement, and, catching my hand, said:

“Now, Rupprecht, I must relate to you the whole story of my life, for you have saved me and it is your right to know everything of me.”

In vain I persuaded the lady to rest and sleep—she, it seemed to me, did not even hear my words, but, firmly clasping my fingers and looking away from me, began to talk quickly—quickly. At first I did not understand her speech, with such impetuosity did she pour out her thoughts and so unexpectedly did she turn from one subject to another. But gradually I learned to distinguish the main flow in the unrestrained torrent of her words and I realised that she was, actually, telling me of herself.

Never afterwards, even in the days of our most trusted intimacy, did Renata relate to me so consecutively the story of her life. True, even that night, not only did she keep silence about her parents and the place where she spent her childhood, but even, as I later had the opportunity of convincing myself without doubt, she in part concealed many later events, and in part related them falsely—whether intentionally or owing to her weakness I do not know. None the less, for a long time I knew only of Renata that little she related to me in this feverish story, therefore I must give it here in detail. Only, I cannot manage to reproduce exactly her disordered speech, hurried and disconnected, I shall have to replace it by a colder narrative.

Naming herself by that single name which alone I know, even to this day, and mentioning her first years so perfunctorily and obscurely that her words were not retained by my memory, Renata at once came to the event that she herself considered fatal to her lot.

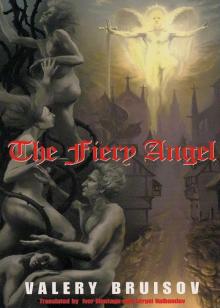

Renata was eight years old when for the first time there came into her room, in a ray of sunshine, an angel, as if all flaming, and clad in snow-white robes. His face shone, his eyes were blue as the skies, and his hair as of fine gold thread. The an

gel named himself—Madiël. Renata was not frightened in the least, and they played, she and the angel, all that day with dolls. After that the angel came often to her, nearly every day, and he was always gay and kind, so that the girl came to like him better than her relatives and playmates. With inexhaustible inventiveness did Madiël amuse Renata with jokes or stories, and, when she was upset, he comforted her tenderly. Sometimes with Madiël came his comrades, also angels but not flaming ones, clothed in capes of scarlet and of purple; but they were less kind. Strictly Madiël forbade Renata to tell anyone of his secret visitations, and even had Renata disobeyed his request, no one would have believed her, for they would have thought her lying or pretending.

Not always did Madiël appear in the image of an angel, but often in other guises, especially if Renata had little time to be alone. Thus in summer Madiël would often fly to her as a huge flaming butterfly with white wings and golden antennæ, and Renata would conceal him in her long tresses. In winter he sometimes took the shape of a distaff, so that the girl could carry him with her everywhere without parting from him. Sometimes, also, Renata would recognise her heavenly friend in a plucked flower, or in a tiny coal that fell out upon the hearth, or in a nut that she broke with her teeth. At times Madiël would come into Renata’s bed and, snuggling to her like a cat, pass with her the time till morn. During such nights the angel would carry Renata away on his wings, far from her home, and show her strange cities, famous cathedrals and even the shining abodes that are not of this earth—and at daybreak, without knowing how, she would always find herself again in her bed.

The Fiery Angel

The Fiery Angel